The ancient Livonian folk calendar was divided into two parts – summer and winter – and the division between these was based not based on the astronomical solstice, but rather on the return (or awakening) and departure (or hibernation) of migratory birds.

Important dates on the Livonian folk calendar

Vastālovā has no fixed date and occurs between February 9th and March 7th, as it is associated with Easter. In Latvian this holiday is called Meteņi and it is similar in form and timing to Mardi Gras and Shrove Tuesday celebrated in other countries. Vastālovā was a final chance to enjoy special foods and have some fun before Lent. Livonians as well as Latvians would go mumming on this holiday.

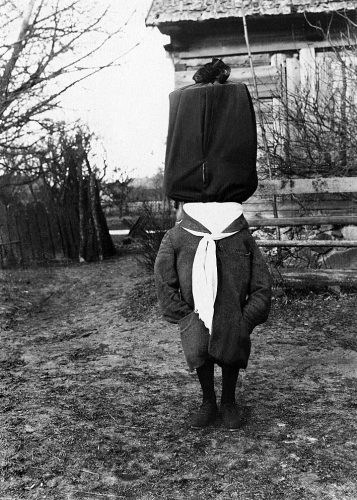

Mask of a crane. Vaide, 1928.

Easter (Lejāvõtāmõd) may have been the central holiday of the year for Livonians in ancient times. On the first day of Easter an offering – spirits, sugar, or white bread – would be taken to the Sea Mother. The so-called bird waking ceremony would also be performed. During this ceremony, participants would sing the bird waking song Tšitšōrlinkizt, which had the qualities of a magical incantation. The song’s central theme was an appeal to the birds imploring them to wake up after their long slumber (the Livonians, and also other nations, held the belief that birds did not fly away during the winter, but instead hibernated in some hidden place). Other important themes in the song included enchantments ensuring a successful fishing season; enchantments relating to farm animals and birds; enchantments relating to young women and men. It was believed that there was a fixed amount of good available in the world. Therefore, when appeals were made for the village to have fat flounders, healthy livestock and birds, beautiful and hard-working young women and men, this meant that neighbouring villages could, of course, only have lean flounders, wolves, bears, lazy young women, and worthless young men.

Midsummer’s Day (Jōņpǟva, lit. John’s Day, June 24th) is considered an important holiday, but its traditions are less interesting than those associated with Easter. Midsummer’s Day was intended to secure the health of crops, which was ensured by decorating the fields. Young people were more interested in dancing and predicting the identity of their future spouse on this holiday.

The Fall Equinox (Mikīļpǟva, lit. Michael’s Day, September 29th) is the most important holiday in the fall. Livonian fishermen would not go out to sea on this day. The inside of the granary would be swept to scare away any rats and as a sign that the summer’s work had ended. The harvest had to already be in the grain bins and it was important to clear the area of any harmful pests. The period from the Fall Equinox to Martinmas was also the season when it was believed the souls of the dead would return home and so food would be left out to feed the spirits of loved ones. The food would be taken either to the sauna or left inside on the stove or a table.

Martinmas (Maŗtpǟva, lit. Martin’s Day, November 10th) ushered in the end of the year. This is when livestock would be slaughtered, sausages made, beer brewed, and pies baked. Mumming was one of the colourful traditions associated with this holiday. On Martinmas it would typically be mostly young men who would go mumming. They would dress up in frightening costumes and ask children to demonstrate their reading abilities and knowledge by saying prayers and repeating psalms. The children who failed these tests would be punished with switches. Jokes would also be played on young women. The Martinmas mummers would say that they had come from Saaremaa. The mummers’ responsibilities included singing, dancing, and playing music.

Mask. Mazirbe. 1928.

The traditions of Katriņpǟva (lit. Catherine’s Day, November 25th) were primarily associated with women and were connected with beauty and the colour white. Young women would go mumming and wear white dresses, men’s shirts, or just cover themselves with sheets on this holiday. Sometimes the mummers would mimic a particularly loud and festive wedding procession. Katriņpǟva was not celebrated much among Latvians, but it was well-known all across Estonia.

Mumming was also a part of the celebrations on Bārbanpǟva (lit. Barbara’s Day, December 4th). As on Katriņpǟva, the young women of the village would go mumming, but on Bārbanpǟva wives and children were known to go mumming too. Mumming on Katriņpǟva was intended more as entertainment and an opportunity for young people to meet each other, but on Bārbanpǟva it was connected with creative magic. However, Bārbanpǟva was connected most of all with sheep and their good fortune. It was expected for the coats of newborn lambs to have the same colour as the mummers’ costumes.

Niklõkspǟva (lit. Nicholas’ Day, December 6th) was considered by the Livonians the beginning of the astronomical winter. Livonians, just as Latvians, associated this day with horses. In order to guarantee good fortune in all horse-related matters, it was common to dress up a young man in a horse mask and take him around all the village households.

New Year’s Day (Ūžāigast, January 1st), just as in other neighbouring nations, began to be celebrated as marking the beginning of a new year only recently. In the past, Christmas (Taļžpivād, December 25th) had been considered the beginning of the new year with the Christmas season ending on Three Kings’ Day or Epiphany (Trikūmpǟva, January 6th).